|

EARLY

HERITAGE OF THE T'AI CHI CH'UAN SABRE

|

|||

|

Like

other civilisations there are no clear accounts of early fighting methods

or weaponry in the Chinese stone age. Weapons existed before Chinese

calligraphy was invented and their origins were usually attributed to

early mythical rulers. |

|

||

| The

sword originated from the pointed stick, a weapon used for throwing

or thrusting, which we know as the spear. If a spear is thrown the enemy

could always throw it back so a hook or barb was introduced to capture the

flesh. In the spear we find the origins of the sword because in fighting

with the spear the top inevitably is broken off and becomes useful as a

dagger. There are many types of spears; double pointed, crest shaped, pronged

and double edged. The first recorded use of a dagger was invented by Chuan

Chu (6th century BC) it was one foot eight inches in length and in even

earlier times the edges were poisoned. Earliest daggers were made of green

jade with a blade three inches wide. A combination of the battle axe with

spear makes the Halberd. The end of a halberd when broken off in battle

gave rise to the broadsword or sabre. The broadsword proper was only really

possible after the development of strong metals. Imagine trying to wield

a sword made from gold and its cutting properties. Eventually the broadsword

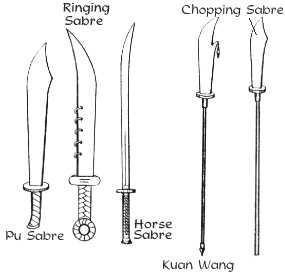

developed in two popular forms a short sword which was worn on the side

of the thigh and a long sword worn at the waist. However, the length of the sabre is known to have varied from two to ten feet depending upon its function. Following the Chinese philosophy of yin and yang they were considered either male or female. Sometimes honorary titles and supernatural powers or attributes were ascribed to exceptional swords such as shining in the dark or the ability to cut jade without dulling the edge. From the time of the Chin and Sung dynasties the emperors sword had a black sheath adorned with silver and golden flowers. The sabre was decorated extensively, ornamentation usually consisted of naturalistic scenes. Many of the ritual and ceremonial swords having engravings of figures of dragons birds, flowers, bears and symbolic seals. In early military thinking the sabre was seen as an important agent of peace. |

|

||

CORE TECHNIQUESThe core techniques involve parrying to the eight directions both above and below, hacking, slashing, pressing, pushing, encircling, slapping, binding, using the pummel and guard to strike and disable. Hooking is an unorthodox though effective technique at an advanced level. Some of the Tai Chi Chuan open hand set techniques would be naturally incorporated as and when required such as kicking, single/double punch and shoulder stroke being most common. A distinctive sabre technique which is typical of the grace and flow of Tai Chi Sabre can be seen in the Neck Flower. The sword player employs this four corner technique by spiralling the sword down and around the back of the body covering above and below with the dull edge towards to body to deflect attacks from the eight directions.

In sabre play the emphasis is on the development of sticking energy to connect with and redirect an opponents attack. Sabre technique can be considered as a natural extension of pushing hands technique. Realistic development of the sabre is dependant on flexibility, dexterity, lightness, and the extension and contraction of energetic awareness without the preoccupation of handling a "weapon". |

|||

GUIDELINES

FOR PRACTISE

|

|